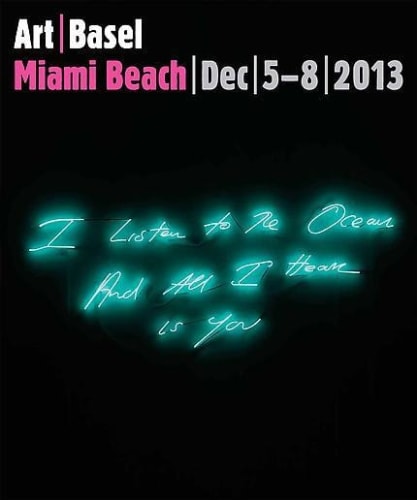

Cover Her in Neon

By: Dorothy Spears

If you happen to see a slightly eccentric blonde, pedaling toward a local Publix or flashing her famously crooked smile at a traffic cop, you may well have spotted Miami’s new It girl, the controversial and irrepressible artist Tracey Emin. Having recently celebrated her 50th birthday, Emin is now enjoying her first American solo museum show, “Tracey Emin: Angel without You,” which opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami on December 4. In celebration of the show, a retrospective of the artist’s renowned neon pieces, the Fontainebleau Miami Beach has adorned towels with the words “Kiss me, Kiss me, Cover my Body in Love,” a message from one of her featured works. She is also one of four honorees at this year’s Women in the Arts luncheon, on December 6. And, as if to formally declare her affection for these seaside climes, where MOCA’s former director Bonnie Clearwater has long championed her work— and where, as her Manhattan dealer David Maupin said, “I think it’s safe to say Tracey feels the love”—Emin has bought an apartment near South Beach.

Since the coveted purchase a little more than a year ago, Emin says she’s visited her new place several times, on her own. “I send lots of postcards with little arrows saying my apartment’s here,” she says during a recent interview. “The rest of the time, I just sit on my terrace looking at the sunset.” She also takes frequent bike rides, pedaling past towering palms and boardwalks. “Once, I nearly got arrested in Bal Harbour for cycling on the pavement,” she confesses. “I got let off, because it was really obvious that I was English and didn’t know what I was doing.”

Emin’s brush with the local authorities is likely to elicit a smile on the faces of those familiar with one of the saucier members of the now-revered Young British Artists (YBAs). Having burst onto the London art scene in the mid-1990s with works such as Everyone I Ever Slept With 1963–1995, a dome-like blue tent appliquéed with names that archly included that of her twin brother, Emin then further cemented her reputation as Britain’s bad girl with My Bed, an altar-like installation presenting her own unmade bed, including a tangle of sheets stained with her menstrual blood and other bodily fluids, as well as strewn condoms and dirty underpants. My Bed was exhibited at London’s Tate Gallery in 1999, when Emin was among four artists short-listed for the UK’s coveted Turner Prize. This was when she appeared, famously drunk, on British national television, cursing and saying, “You people aren’t relating to me now. You’ve lost me; you’ve lost me completely,” before staggering off the set.

Emin has been courted by the British press ever since (they clearly relish her penchant for grandiose self-exposure) while making work in a range of media that often provocatively addresses sex—an appliquéed blanket bearing the words “Psycho Slut,” drawings of supine nudes—often herself—with fingers fondling the area between splayed legs, as well as a brutally vivid video describing her own botched abortion.

Emin’s influences range from the artists Johannes Vermeer and Egon Schiele to her own father, a Turkish Cypriot. “You know, I’m not Anglo-Saxon,” she says. “My heritage comes from a completely different place. So I’m very romantic, I’m very passionate, I’m very hot-blooded.” It could be precisely this unusual alchemy of antecedents that makes her work—whether she’s tapping into lust or loss, happiness or heartbreak—convey a warmth and honesty that speak to such wide audiences. As the Miami collector Barbara Herzberg, a former cardiac nurse, recently noted, “I worked at the county hospital where the majority of people who came in were immigrants, refugees from Cuba, and homeless people. I didn’t know them personally. I didn’t know what their lives were like. But I knew their hearts.” Seeing Emin’s 2012 neon wall piece When I hold you I hold your heart, Herzberg says, “I felt as if Tracey made that for me.”

Celebrities as varied as Elton John, David Bowie, Madonna, and Joan Collins have also all gravitated toward Emin and her work because, as the artist herself bluntly puts it, “I’m popular culture, that’s why. Artists in the UK are as well known as actors, or supermodels, or musicians. They’re on the front pages, on the back pages. During the World Cup, artists are on the sports pages quoted talking about football.”

After a pause, she adds reflectively, “Maybe that’s why I like being in Miami.”

One of her greatest pleasures when she’s in town, Emin confesses, is cycling around and thinking, No one in the whole world knows where I am right now or what I’m doing. Of course, “Angel without You,” a retrospective of more than 60 neon sculptures, is likely to change that. Curated by Clearwater, who recently became director of the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale at Nova Southeastern University, the show, which runs through March 9, 2014, includes a single video, Why I Never Became a Dancer. A raw but oddly uplifting meditation on Emin’s adolescent encounters with sex in the seaside resort of Margate, where she grew up, the work was purchased by MOCA in 1998. “I responded to it right away, and every time I watch it I smile,” says Clearwater. “It’s almost like why Tracey never became a dancer... was why she became an artist.”

Neon signs, typical of those in many seaside resorts, can be seen in the video and, according to Clearwater, make the piece a fitting introduction to a show devoted exclusively to works in this medium. “Tracey’s hometown of Margate is filled with neon. And of course there’s neon in Miami. So, again, it made a lot of sense, this connection.”

Emin agrees, adding, “This is a pure neon show, in a very simple way, and unapologetic,” a fact that adds to its novelty. Even in the case of artists such as Bruce Nauman who often work in neon, she points out, she’s never seen a 17-year retrospective composed entirely of neon works.

The neons at MOCA present evocative phrases and snippets of thoughts writ large in Emin’s inimitable hand, which again speaks to her personal history. “My handwriting is quite old-fashioned and joined up in italic and elongated letters. All my family writes like that on my mum’s side. I think the writing is very fluid, and it’s very much like my drawing. So when I write a sentence that’s a neon, it’s actually a drawing I’m making of the sentence.”

Although Clearwater noted that the neon works mark a shift away from the confessional, diaristic tone of Emin’s earlier pieces, Emin herself puts it a little differently. “They’ve shifted away because they’re neon, and because they’re spangly, and because they look beautiful,” she says, “so people see the glory and the beauty before they see the words. They see the light before they see the meaning.” Still, according to the artist, the words are heartfelt. “I make them because they're inside of me."

A phrase from a letter, or a thought she’s had about someone, or something she’s witnessed, can all result in a neon piece. “I dance a lot alone,” she offers, “and I listen to music and lyrics. And then I mix the lyrics all up in my head, so some of my neons sound like lyrics.” The messages are intimate, but as Maupin points out, “The work is really about a universal experience.”

“Angel without You” will be accompanied by items from Emin’s online store, Emin International, as well as beach towels made in collaboration with the Fontainebleau Miami Beach and flip-flops sold at MOCA’s shop. “Tracey wanted to do objects specific to Miami,” says Clearwater.

The limited-edition, 100 percent velour cotton towels are black, with the actual image of Emin's work Kiss me Kiss me Cover my Body in Love reproduced in neon pink. They retail for $95 at a Shops at the Fontainebleau pop-up store in the hotel lobby during Art Basel in Miami Beach. To promote Emin’s exhibition at MOCA, a dramatic aerial photograph announcing the collaboration will include nearly 1,000 lounge chairs and cabanas surrounding the hotel pool, draped with these signature towels. The flip-flops, according to Clearwater, feature another neon phrase embedded in their soles, so that the botom of the shoe will leave an impression of Emin’s

words in the sand.

In keeping with the majority of neons on exhibit at the MOCA show, the message of the 1996 work Kiss me Kiss me Cover my Body in Love is “really about love and about positive feelings or an interest in positive feelings,” Emin notes. Compared with the unabashedly raunchy work that first set her course as an artist, an exhibition focused on the theme of love may seem chaste or even suggest a certain mellowing. Yet for an artist so consistently attracted to the edgy thrill of emotional striptease, the topic of love is likely to be quite fraught. Either way, Emin remains as upfront as ever about addressing cultural taboos, including one that dovetails a more recent aspect of her personal life: menopause. In an interview last year, Emin boldly told a reporter at the Guardian, “People don’t talk about it, but the menopause, for me, makes you feel slightly dead, so you have to start using the other things—using your mind more, read more. You have to be more enlightened, you have to take on new things, think of new ideas.”

Among these new things, apparently, are bike rides along the promenade, a bit of reflection, and a place in Miami with a nice view of the sunset.