Mickalene Thomas: Afro-Kitsch and the Queering of Blackness

By Derek Conrad Murray

The rearticulation of African American identity emergent in contemporary art suggests that existing notions of blackness have underrepresented-or completely failed to represent-constituencies within the community whose experiences are not encapsulated by civil rights and Black Power-era value systems. Particularly, the historical emblems and visual markers of heteronormative blackness may not speak to the lives and identities of individuals whose gender and sexual orientations often position them outside dominant understandings of black identity. This examination of the New York-based artist Mickalene Thomas's work opens up a needed conversation around post-blackness and its significance in visual culture as an iconoclastic queering of blackness. Post-black discourse questions the ideologicaI parameters and visual rhetorics of blackness as potentially alienating and noninclusive of gender and sexual difference.

The term "post-black" emerged in a casual conversation between the artist Glenn Ligon and the curaror Thelma Golden in reference to the latter's Freestyle exhibition, held at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001. Since finding its way rather inauspiciously into the art world's consciousness, it has produced a discourse all its own and is hotly debated to this day, inspiring journalists and cultural critics outside the visual arts to ponder the term's larger social impacts. The journalist and author Toure's recent book, Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness? What It Means to Be Black Now (2011), follows Ytasha L. Womack's 2010 effort titled Post Black: How a New Generation ls Redefining African American Identity. Both texts boldly embrace the challenge of redefining black identity beyond a monolithic pride that has been reduced to essentialism, self-ghettoization, and compulsory racial politics. The result has been the emergence of a divisive intracultural debate about post-racialism and the policing of proper blackness by what Touré calls America's "self-appointed identity cops"

within the African American community.

Post-blackness resonates because it articulates the frustrations of young African American artists (the post-civil rights generation) around notions of identity and belonging they perceive to be stifling, reductive, and exclusionary. For many, blackness is a nationalist cultural politics that produced a set of values and visual expressions overly concerned with recovering black male dignity-by advocating for traditionally heterosexual archetypes of patriarchal strength, domination, and virility. Post-blackness can also be understood as issuing from a general attitude of ambivalence toward compulsory solidarity, insularity, and intracommunity demands to maintain a sense of racial pride. There is a broad rejection of both the generational passing down of racial trauma and the expectation that the post-civil rights contingent will carry the torch of survivorship through the uncritical valorization of past anti-racist movements. The elusiveness of post-blackness makes it difficult to fully define, and certainly not all African American artists grouped under this banner can easily be encompassed by it. It is more of an ethos than a dictum; nevertheless, it continues to define a generation of artists, many of whom seek to escape the limitations imposed by race.

The prevailing criticism of the pose-black ethos is that its artists are enthusiastic participants in the market and gleefully indulge in the glittery spoils of success at the expense of meaningful social engagement. Post-black visual art-exemplified by the work of Thomas, Kehinde Wiley. Laylah Ali, Iona Rozeal Brown, Kori Newkirk, and, more recently, Kalup Linzy and Rashaad Newsome-has fully embraced the extreme marketability of black corporeality. Often, it deceptively seems to present cleverly constructed visual quips that use the black body to create readily salable objects. This is not asserted to discredit the work. Quite the opposite is true. African American artists produce their work in an enduring climate of racial hostility and dismissiveness, and in conditions where the very notion of black artistic achievement is continually called into question. Post-blackness speaks to a desire for creative freedom and a need to liberate oneself from the often-suffocating nature of racial polemics. It simultaneously articulates a departure from a heteronormative definition of blackness that was often restricting and negating (i .e., civil rights and Black Power Movement representations). African American art in the 1980s and 1990s was politically oppositional vis-a-vis the dominant white, patriarchal culture and overtly concerned with the effects of intolerance on black subjecthood. These concerns, now largely abandoned, have given way to an aesthetic that appears very similar to former expressions, only drained of didactic political or historical content. As a type of collective consciousness, post-black represents a satirical and often contradictory engagement with the normative signifiers of blackness, one that renders it strange, unknowable, and open to the process of signification: a queering of blackness, so to speak.

The term "post-black" also seems to convey the psychic dualities, the “two-ness" that W. E. B. Du Bois speaks about in his notion of "double-consciousness."; Golden described post-blackness as a type of cognitive dissonance, whereby emergent African American artists produce work about blackness bur simultaneously seek to transcend the limitations often imposed by race. What strikes me as more urgent, however, is that post-blackness represents a crisis in black art production that issues from a desire to be liberated from racial polemics, nostalgia, and belongingness, while trying to negotiate a voracious market demand for the black body. This represents a conundrum of sorts. African American artists born in the 1970s and later are particularly impacted by this existential crisis, because many have shed communal bonds and comforts of membership by not conforming to "heritage" representations that foreground cultural preservation, even though commercial interest in the persistent visualization of blackness is more fervent than ever. What happens when an African American artist no longer sees the critical potential of the black body, or has become disinterested in the political and polemical importance of its imaging? Are what one sees on the walls of galleries and museums across the United States conceptually clever and visually rich depictions of abject blackness that are ultimately empty signifiers?

In the wake of the Studio Museum in Harlem's Freestyle exhibition, there was a palpable sense that black art (and its discourses) had shifted formally, conceptually, and intellectually. However, this change was also evidenced by the greater presence of women artists, whose engagement with the intersection of race and feminist representational politics produced striking results. The painter and photographer Mickalene Thomas is one of the most celebrated of Golden's roster of post-black artists. Thomas's spectacularly colorful and decorative images explore pictorial strategies around African American women, taking on such themes as femininity, celebrity, sexuality, and power, while simultaneously sending up the Blaxploitation aesthetics of 1970s black visual culture. This is achieved through cultivation of an effective tension between her painterly investments in discourses of form and the inevitable moral thicket of engaging representation of the black body. The artist's mixed-media painting Hotter than July depicts a reclining black female nude in a seductive mode: breasts partially exposed and mini skirt hiked up. The figure stares into the distance wantonly, with that slightly detached and glazed-over expression common in soft-core pornography. Painting with dull brown, using no modeling to articulate form and volume. Thomas chose a decidedly graphic approach to image the black body. This flatness situates her work within a history of African American figurative painting from William H. Johnson to Kerry James Marshall, though Thomas's paintings feature women exclusively. In Thomas's kitschy mise-en-scene, the arrangement most aptly recalls a still image from a Blaxploitation film. The background, painted in muted yellow ocher and purple, has the tacky cheapness of a 1970s porn set-while the woman's pose is pure, languid, orientalist fetishism. The only articulated figurative elements (clothing, eye makeup, and afro) are rendered with flat acrylic color and rhinestones that convey a type of tawdry regalness.

Conceptually, Hotter than July employs a combustible, albeit satirical, mixture of intellectual references, from feminist critiques of European modernism and critical race discourse on Blaxploitation aesthetics to orientalism-not to mention its titular reference to the musician Stevie Wonder's 1980 album of the same name. Bur Thomas's work is perhaps most concerned with the depiction of African American women. Her images are critical of the exploitation and commoditization of black female bodies by the dominant culture, but there is also something disturbingly urgent about the intracultural dialogue she engages around the way black people depict themselves. It is important to remember that Thomas is a woman painting other women, an act that positions her within a lineage or feminist representational strategies, whereby women (as image makers) aggressively claim agency and control over the female body in an oppositional act of self-representation.

Works such as this one are not concerned with chastising the objectifying manner in which men look at women; rather, they are more explicitly concerned with the black female gaze (empowered female looking). Hotter than July takes on many of the stylistic tropes of heteronormative sex images and rearticulates them through a distinctly queer-feminist desiring lens. The queering, however, is also a means or rendering the black body strange: of giving it a signifying potential chat allows the possibility for new meanings to be constructed. In Hotter than July, the black female form is elevated above and beyond the object status typically assigned to the types or visual forms it references. Thomas endeavors to present a new black female subjectivity that (at its most effective) is both defiant and playful, even as it directs a critical lens on the culture that has alI too often neglected or objectified the bodies of African American women.

Thomas's work reflects the shift in black art from didactic political narrative to post-black satire, particularly in regard to her rearticulation of fetishistic representations of black women. Her images critique American media culture's debasement of black women. bur they simultaneously take aim at misogyny within the black community, particularly in the male-dominated 1970s Black Power era. The rise of satire in post-black visual art-particularly in the creative production of black women-is notable when considering the literary genre's history. As Darryl Dickson-Carr has observed, satire has tended to be most associated with and dominated by men. Within the literary tradition, he writes, "women have often been dismissed as sexual objects, decried as ideological femmes fatales, and assigned a hefty part of the blame for the demise of civilized discourse in at least a few African American satires." Satirical wit is one of the primary and most incendiary characteristics of post-black production created by women and queer artists, because it approaches not only the subject of societal racism but also the enduring problems posed by black intracommuniry chauvinism and homophobia. It achieves this by mobilizing a unique quality of effective satire: it can simultaneously operate as both critique and self-critique.

The sexual and gender policies implicit within post-black aesthetics have not yet been fully unpacked. Many of the most prominent post-black artists are women and gay men, whose diverse products utilize the black body (and the visual culture of blackness) as image-not in an overtly political manner but, rather, as an image of mythical resplendence. Considering the "pose" of post-black in relation to the work of African American women artists poses a series of interesting questions. Their artworks often straddle the fault line between feminist consciousness and racial allegiances and express an uneasy relation to both. What results is a lessened commitment to what Amelia Jones calls the performative female body that is common in earlier forms of feminist art. Specifically, Thomas and other black female artists appear less interested in a specifically male-viewer/female-viewed matrix that has become a linchpin of women's oppositional aesthetics. Thomas's work is unapologetically formal-almost aggressively so-and is perhaps more motivated by the pleasures of the visual (which could be read as "masculinist” or "universal" in the sense of universal formalism) than by an engagement with the abuses of the patriarchy. Nevertheless, the gesture to radically colonize the formal could be read as stridently feminist. The irony in Thomas's painting, for example, has a dual function: to expose the hypocrisies of racial fetishism and to liberate the work from identity policies that have become outdated.

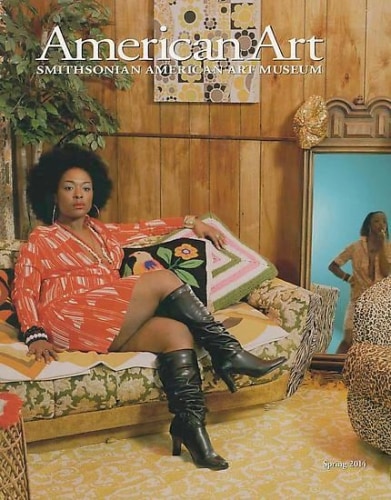

A question that often emerges is whether these cultural workers are disconnected from mainstream feminism and estranged from dominant understandings of blackness. In some instances, the post-black production of women artists appears to constitute a radical rethinking of feminism, one that reconsiders the notion of feminist agency as an act of creativity. Thomas's Sista Sista Lady Blue, from Odalisque, for example, positions the black female body somewhere between racial fetishism and feminist transgression. The color photograph is reminiscent of 1970s soft-core pornographic imagery, Blaxploitation films, and modernist masterworks such as Edouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1882). A dominant figure, a woman wearing a red and white dress and black knee-high heeled boots, reclines in a loveseat in an interior space filled with competing textures of wood paneling, houseplant, art, and wallpaper, along with densely patterned furniture, throw pillows, and carpeting. Her large black afro frames an attentive, commanding look aimed directly at the viewer. Behind her and to the right stands a tall, wood-framed mirror that reflects the image of a second woman in a partially unbuttoned dress taking a drag off her cigarette. A triangulation of gazes passes between the photographer at the moment of capture (whose perspective becomes that of the viewer), the foreground subject, and the woman reflected in the mirror. Just as Manet’s Bar depicts the reflection of a bourgeois male spectator, the complicated configuration of looks in Sista Sista Lady Blue suggests that the presumed viewer is the second woman-a black woman at that. Thomas's playful visualization of black female spectatorship encourages the viewer to pleasurably occupy otherness while disidentifying with that state at the same rime. In a sense, the viewer gives in to the commodity spectacle of difference, while simultaneously having both his/her desires and revulsions indicted. This push/pull of pleasure and guilt resonates in the artist’s work, denying the viewer a chance to sit comfortably with her imaginings.

In Thomas's photographs and paintings, the charade of beauty is in violent struggle with the complexities of identity. The formal and the political comprise dueling expressions of identity politics, each performing an essentialist masquerade while remaining concealed under their respective veils. Thomas's depictions of the black female imago are not just symbols of objectification: they are also reminders that the content/form opposition represents irrecoverably fundamentalist positions in the visual arts. Among the discursive powers of Thomas's art is its facility in turning the gaze on itself. The artist is keenly aware of how recognition interpenetrates viewership when the signifiers of race are visualized. The black female body as rendered in Sista Sista Lady Blue is an intentional marker of cultural difference and a mode of representing otherness. Unhinged from the overbearing burden of race discourse, her ornately rendered black body- and the bodies of Thomas's other female subjects-becomes a concentrated object for consumerist consumption, as well as a painfuIly uncomfortable meditation on its visual presentation. It hovers in the realm of the uncanny, the familiar made strange, especially in the instance where its queered subject position effectively displaces the viewer's.

A Little Taste Outside of Love (fig. 3), a colorful painting that adapts its title from the equally vibrant Millie Jackson song, is classic Thomas. A lone female figure reclines on a decorative sofa, surrounded by ornately designed duvets and pillows. The woman's posture echoes Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's 1814 Une odalisque (La grande odalisque), in which a concubine presents her backside while gazing impassively almost defiantly-at the viewer. In the case of Thomas's figure, brown skin and ample afro convey protestation that somehow undermines the mise-en-scene, while still remaining seductive. All the politically correct elements are here: the nod to feminist art historical revisionism, the orientalist critique of racial fetishism, 1980s- and '90s-style identity politics, and the self-conscious send-up of Afro-kitsch. There is enough conceptual meaning to satisfy the intellectual pretensions of art world aficionados and budding art historians the world over. The painting oozes cool. It is a spectacle of black hipness, an aesthetic expectation that all African American art must fulfill just to be considered. Thomas surely knows this, and so she supplies all of the requisite flash. The black body is made available in all its embattled grandiosity-reified into a phantasmagoria of racialized tackiness. But these elements are deceptive, if we just look beyond the candy-coated exterior and the conceptual wrangling that function merely to obfuscate and misdirect. The complex compositional elements, the ocher yellows, grays, and browns, all tell a different tale, one steeped in formalism and materiality. Thomas is a painter first and a moralist second-a fact that belies the expectations placed on black artists: that they must instruct with racial didacticism, even in the face of punishment and public shaming for doing so. The art world wants its black bodies big: larger than life, whimsical, and colorful-presented within the stylistic tropes of Western high art as a sight gag, the melding of high and low, the ghetto and the glam. In this regard, Thomas is in the terrain of her contemporaries Kehinde Wiley, Yinka Shonibare, and Rashaad Newsome, but in her feminism resides something that is perhaps more incendiary. In its reference to Millie Jackson's hit song, the title speaks to the temperament of a fed-up black woman, one who dumped her man for cheating on her. The lyrics are at once bitter and bold, melancholy and empowering. It is a narrative of struggle, of finding one's beauty and strength from within and in the face of persistent negation, neglect, and abuse. The formal is perhaps the epicenter of that defiance, the tool of resistance-even more so than the returned queer-feminist gaze. In Thomas's paintings, the black female body is often alone, isolated, a sight of viewing pleasure, but also impudent and disobedient. Imagine black power as a purely feminist intervention, as a formalist oppositional space. Thomas's images function in this manner: as satirical meditations on the intersection of gender, race, and form-all with a hint of queer desire. Dickson-Carr suggests that satire always "manages to fascinate, infuriate, and delight us to the extent that it transgresses boundaries of taste, propriety, decorum, and the current ideological status quo." Both celebrated and reviled, Thomas's resplendent post-blackness manages to embody all of these characteristics, while simultaneously giving us pleasure and making us rethink the ideological boundaries we ascribe to our identities.